Challenges with lean implementation across multiple sites

The following transcript is from a presentation on the topic of lean implementation to the Lean Manufacturing Special Interest Group held in Adelaide in May 2013 by Mr Peter Gardner, Global Manufacturing Engineering Director, TI Automotive.

The talk focuses on having the right motivation and attitude towards lean implementation, and discusses the use of consistent standards and assessment systems within production sites spread across the globe.

Introduction – Lean Implementation

I’m going to try to share a few of my experiences. We’ll have a bit of an introduction first. I’d like to start by introducing our company with two or three slides as that sets the scene. I’ll ask the question as to why you may think that lean manufacturing is your solution. I’ll provide a little bit of history, I think that’s always helpful as there is a lot of history in lean manufacturing. I’ll talk about what TI Automotive has done, and we’ll finish up with some final comments.

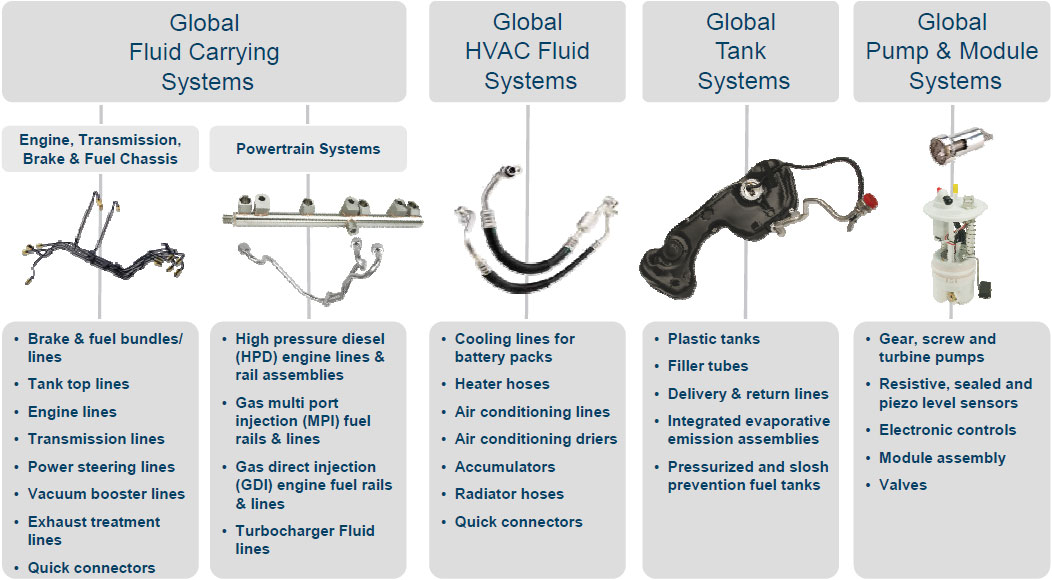

TI Automotive actually has four divisions. We make blow-moulded fuel tanks, pump and module systems for fuel, fluid carrying systems which is the area which I’m involved in, HVAC fluid systems in the engine bay, and power train systems comes under the Fluid Carrying Systems Division.

In the division that I am involved in we make a lot of brake and fuel tubular systems. We make all the plumbing that goes underneath the car from the fuel tank right through to the engine, for both the brake and fuel, for the wheels, ABS units etc. On the power train system side of the business there is a lot of fuel rail and high pressure diesel work. Diesel tubes are now coming in and that’s a very big part of our business. Diesel motors are becoming more and more popular every day.

The company overall has about 130 locations, and I don’t think there is anywhere in the world where motorcars are being built where we don’t have some sort of facility – either a manufacturing facility, a warehouse or a sales office. We have a very wide coverage. The nature of the brake and fuel products, once they are fabricated and assembled ready to go on a car, is such that they are extremely difficult to ship. They don’t package easily and they can be damaged easily, so our philosophy is to have our manufacturing facilities close to where our customers are building cars.

Here’s just a snapshot of the overall size of the company. The Asia-Pacific region represents about 28% of the sales of the total company. That’s rapidly changing – over the past three years the Asia-Pacific region has overtaken the US and in about four years it will overtake Europe. Europe is not travelling all that well at present, whereas the size of the automotive industry in the Asia-Pacific is still doubling about every five years.

Lean Implementation – The Right Attitude

Before you jump into lean manufacturing you need to think about whether that really is the best solution for you. Is there a real need for it, or is it that someone has been to a seminar like this and it has become flavour of the month. If some executive somewhere says that they were at something the other day, and they were talking about lean manufacturing, and therefore we must do a bit of that – well that is exactly the worst motivation to get into lean manufacturing. TI Automotive, coming through the Global Financial Crisis that hit the automotive industry and most other industries pretty hard, came out quite shaky. So during the 2010 to 2012 period we had problems with cost of poor quality, too much inventory, and productivity improvement not where it needed to be. And if we look at those three alone, quality issues, inventory issues and productivity issues, they are the classic needs where lean manufacturing systems should be effective.

I want you to get into it for the right reason. You don’t just assign someone to go off and say “Listen, develop a lean manufacturing system for us and come back when you’re ready.” It really does need involvement from the senior management or the board within your organisation, because unless they are committed to working with you, you will continue to run into problems, because lean manufacturing is not a quick fix solution to problems. You will get sustainable benefits out of it but it may take months or years before these benefits come. This isn’t something that will happen overnight. Unless you’ve got the hierarchy in your organisation well in tune with that line of thinking, you will be in trouble. This is because if the improvements don’t come overnight, I dare say that you’ll be told to shut up shop.

One of the things from lean manufacturing that can trap people; and our company has been through it and I will talk a little more about that when summing up; is a mindset that lean is just a toolbox of tricks. There are a lot of tools that will help you solve problems through lean processes, but the main thing to focus on in lean manufacturing is attitudes. We want our people needing to find better ways to improve themselves, to improve the business, to identify waste in the business and focus on getting rid of wasted opportunities in the business – that’s the starting point. The tools are easy to implement once you’ve got the people on board and understanding that there is a need to improve.

A Brief History of Lean Manufacturing

A little bit of history regarding lean manufacturing is helpful. Even before World War II, Toyota were making improvements in their weaving loom business, and it was back then that the Toyota people realised that improvements made in their business would make not only the cost of their processes more robust and lower, but that it would be beneficial to the people in the business also because their jobs would become more stable. So from those very early days before World War II, improvement and elimination of waste was in the DNA of the Toyota people. Just after World War II when Toyota were in the early days of getting into the automotive business, the Toyota president of the day, Kiichiro Toyoda, stated that Toyota needed to catch up with America in three years otherwise the automotive industry in Japan would not survive. Investigation started as to where the gaps were in Toyota’s business, and it was quickly established that there was a difference in productivity between what they saw in America and at home in Japan of about nine to one, so for every car that the Japanese automotive industry was putting out, the Americans, with the same level of resource input were able to put out nine vehicles.

It became obvious that there was a lot of waste in the process. And this is where a gentleman by the name of Taiichi Ohno came in. He was essentially the architect behind the Toyota Production System, and in the very early days, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, he did a lot of experimentation on the shop floor about breaking down people’s attitudes in the factory about the way they should work.

I can still go into some factories these days and see people that say “well, I work on a welding machine, and I’m trained to do a welding operation, and that’s all I’m good for.” Taiichi Ohno had that challenge in the 1950s in Japan and over many attempts he was able to convince the workforce that it would be better if they could all train in a range of processes so that they could get their materials to flow better through their factory. The people became multi-skilled and the productivity ratcheted up very quickly once that realisation was made.

Toyota has been at this game for sixty years, and even today when you talk to senior Toyota people who are directly involved in the Toyota Production System philosophy they still profess today that they have a long way to go, a lot of learning yet to do, a lot more experimentation required and a lot more improvement to achieve. So lean manufacturing is not an overnight solution. You can get gains fairly early on, but you’ve got to realise that it is a long hard road.

So what did TI Automotive do about this? We worked out we had a need, we understood the history, and we read the literature. If no-one has read the book by Taiichi Ohno (Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production), I would recommend that as your starting point, because that talks about the philosophy behind the Toyota Production System. It’s not a bible on how to do things, but if you read it, and read between the lines too, you can see where the Toyota Production System is coming from. More than anything, do not blindly follow the Toyota Production System, because as the Toyota people say themselves, the Toyota Production System evolved and developed to solve Toyota’s problems, not our problems. Each of our plants has a unique set of problems, and some will be similar to Toyota’s problems, but many will be different. Certainly our products are likely to be extremely different.

So we need to make sure we understand that there is a real need. Get your philosophy clear on what you’re trying to do with your improvement program and lean manufacturing, and get your focus crystal clear.

In the division we are in at TI Automotive we have 86 sites, so we had to have a fairly hierarchical type of organisation to make sure we were inclusive of our whole business when we were launching lean manufacturing. We chose not to set up two or three pilot plants, but instead we chose to do a lot of hard yards behind the scenes and set up the system with consultation with a lot of plants that we could launch globally.

So we set up a steering committee of which there were three of us involved, myself I was looking after Asia-Pacific inputs, we had another from North America looking after North and South America inputs, and we had another from Europe who also looked after eastern Europe and South Africa. So we pretty much had the world covered. The other two were direct operations guys, so they were truly hands-on, whereas my role in manufacturing engineering, whilst very closely associated with the operations, is not directly hands-on. So we thought we had it covered at that level, but we didn’t have all the expertise ourselves, so as we were developing the workings behind the TI Automotive systems we coerced some special teams to look after special areas and provide feedback to us about what was needed as well.

We worked on this without launching into the plants for two years. Part of the reason for requiring two years was because we have such a complex organisation, and I would hope that anyone with a simpler structure could do it much faster. Ultimately we finished up with the TI Productions System, or as we called it “TIPS”. But we weren’t afraid to borrow from TPS and the infamous TPS house, so we built a TIPS House. The roof represents our objective to support stakeholders, customers and employees, and make sure they were satisfied with the outputs of the business. If they were satisfied, we knew the business would be strong.

We built this TIPS process on a foundation of both Kaizen / Continuous Improvement and zero defects. In our business we need to build our product to a takt time, which is the rate at which our customers are demanding products from us. We didn’t want to over produce or under produce, and this required the involvement of all of our employees, especially our shop floor employees. We wanted to have pull systems throughout all of our operations, and I can tell you we have a long way to go there – we’re just scratching the surface. The advantages of pull systems are that they will remove WIP from your process, it will help you manage your finished goods, and it will give you clarity on the shop floor – as problems and bottlenecks evolve you will be able to see them much clearer.

Standards and Assessment

Our brake and fuel business in particular has grown since the 1920s, and one of the reasons that our business has been successful globally is that we’ve given a lot of autonomy to our outposts. They’ve been successful in winning business and servicing their customers. However every outpost was doing its own thing and being successful in its own right. When when of our large global companies came into China and said it wanted the same performance out of China that it was getting out of TI Automotive in Germany, well we didn’t know if that was fair. But if you’ve got global customers, you just say “yes sir” – because their business is good, their money is good. So global standards is a challenge ahead of us at the moment, and that is all consuming for me.

We’ve produced a booklet that has some basics of what we are calling those nine elements from TIPS: the three elements of satisfaction, the four pillars, and the two foundation elements. The purpose of producing that was to be able to give it to the shop floor employees. Then when we came onto the shop floor and talked about having to build to standards and requesting their involvement in implementing pull systems, they had something they could take away to read and to question.

We’ve also produced a manual that is an expansion of the employee booklet. It is not a how-to book, nor a lean manufacturing toolbox, so it does not tell you the day-to-day tasks of how to implement a pull system or how to do SMED or how to do TPM (there’s a lot of acronyms in all of this). Instead, the manual is a set of guidelines about how to operate the business on a daily basis: what you need to do in your monthly management reviews, what you need to do on the shop floor on a daily basis, how to set the shop floor up with information about what’s happening in the business, etc., so that everyone is exposed to the performance of the business.

The reason that we put that into the manual and not the toolkit, is so that when we do a self-assessment of the business we are assessing the way the business is structured and managed for improvement activities. The focus is not the success that they are having with pull systems, or SMED or Kaizen or small group activities, but it is a system that will allow you to measure how you are running the business. And what we’ve done here is split each of those nine elements off of the TIPS House, and within there we have sub-elements as well, split into five categories. Category one is that you are not doing anything associated with what the element requires you to do, up to Category five, where you are truly world-class in your activity in that particular area. And so the plant manager can score his operation on a one-to-five basis.

As we are planning to roll TIPS out across our organisation, this is not a corporate roll-out. This is a roll-out that is putting the onus directly back at the plant level where the improvements need to be. As such the objective and the task is to get buy-in at the plant manager level such that his management team take ownership of the process and roll it out across their plant. Improvement activities must surely be the plant manager’s responsibility. I can’t walk into a plant and say that improvements are needed if the plant manager is standing back and saying that that is rubbish, I don’t want to do this, I have different priorities, etc.

So out of this self-assessment process, where we are analysing the elements and the sub-elements in our system, we can get this score which will automatically give us a gap analysis. Anything less than five tells us that we have a gap, so if we are down in the twos and threes, then that’s where we should put our priority. If we are four then we can probably live with that for a year or two, because I can assure you that we will have twos and threes elsewhere, but hopefully not too many. Ultimately the gap analysis can be presented anyway you like. We are choosing to do it with a spider diagram so that we can see where the highs and lows are. There are also some improvement plan activities and a timing plan that go together with the self assessment.

The other big advantage of the scoring system that we are bringing in, is that it will allow us not just to identify improvements required in one plant, but it will help us share knowledge across all of our plants. So we might have a group of plants across India that are struggling across one particular element and have twos and threes, but we might have a plant in Spain that has fours and fives in that area, so we can get the two of them talking together, or use myself as a conduit, to understand what the team in Spain is doing to get fours and fives, and what is being done in India to get twos and threes. We can bring that information together, and that way we feel that we can very rapidly deploy the very good things we are doing in our business, bring the ones, twos and threes up to fours and fives, and achieve results quicker.

Implementing Lean – Final Comments

I read a lot of material on this subject, because I personally find it fascinating and challenging to find the best ways to help us in our business. There’s currently a lot of information coming out of North America about Six Sigma being a lean tool. Six Sigma definitely has a place for problem solving in business, but my definition of a truly lean tool for help improve your business is one that can be applied at the factory floor level involving the factory floor people. Six Sigma does not easily lend itself to applications involving people directly on the shop floor driving improvements. There’s a place for it, but I don’t put it in the same category as lean manufacturing.

Six Sigma does not easily lend itself to applications involving people directly on the shop floor driving improvements. There’s a place for it, but I don’t put it in the same category as lean manufacturing.

I’ve already touched on focusing on attitude and not on the toolbox of solutions. In one example out of our own business in the US some fifteen years ago, we launched what we then called Common-Sense Manufacturing, which is really just a local name for the Toyota Production System or lean manufacturing. Essentially we went into it very heavily with lots of tools and lots of training on how to use the toolkits, but over the last fifteen years, as people have come and gone, and as we’ve had to squeeze head count in North America during the Global Financial Crisis, we realised that there was no substance underpinning the lean manufacturing processes that we put in there. We hadn’t changed the culture in the factories. We were doing some good work in how we were using the tools, but we hadn’t changed the culture. And really that’s where a lot of effort has got to go.

Regarding communications with stakeholders, it is absolutely critical to keep your senior management and board involved. You don’t want any surprises when implementing lean – if you’re running late or coming up against any budgetary constraints, get it out there and get it out there early. Lean implementation is a long-term program, not a quick-fix overnight.

Be aware of cultural differences. I get exposed to this a lot in Asia, where some of the Asian cultures are very strong, especially within Japan, China, India and Thailand. When working inside our factories I don’t try to change people’s country culture – you’ve got no hope. But inside the factory there is a company culture as to the way we do things, and we’ve got to work with that company culture and the country culture to find some middle ground. You cannot just impose one on top of the other. If you just let the company culture rule, and we’ve been there in particular in China and Thailand, and if the company culture tries to bulldoze its way through, your success rate will be very slow.

But it’s not just country culture that you need to be aware of. There are regional issues, and North Americans don’t like the Europeans, who don’t like the Asians, etc. And so there’s a whole lot of work that has got to be done within your own organisation. Even plant to plant – I remember when I started here with TI Automotive I was the General Manager of the Australian operations and couldn’t believe the differences in attitude between our plant in Dandenong, Melbourne, and our plant in Kilburn, Adelaide. Just 750 km apart there were differences in attitudes, differences in culture and differences in the way people did things. It’s very important that you are aware of these things early before they start to fester and undermine your activities in your lean implementation actions.

I would highly recommend that you find the book by Taiichi Ohno, it’s probably around $40 and well worth the investment. There’s another guru from the 1950s and 1960s out of Japan, Shigeo Shingo, with a very good range of books on toolkit activities such as Poka-yoke, Single Minute Exchange of Die, and some basic production process techniques. Another good source of information is the Lean Enterprise Institute.

I would highly recommend the Shinka Management team and their association with the Japan Management Association Consultants (JMAC). I have used them myself and I can’t speak highly enough of their capabilities.

There’s a heap of information on lean manufacturing. Be careful you don’t get swallowed up by it all. Be careful you don’t jump into the toolbox solution too quickly. Be careful you don’t get bogged down like our company did taking two years working out want to do before implementing it. Roll your sleeves up and get stuck into it cautiously. Plan, plan, plan and then implement fast. And once you start implementing I think you will find the benefits and it will be very, very rewarding.

The Lean Manufacturing Special Interest Group meets regularly at locations across Australia. Meetings are facilitated by Shinka Management lean consultants.